Trapped in the Dark: 4 Real Cave Stories of Explorers Who Never Came Back

Exploring caves is one of the most demanding and at the same time most dangerous forms of adventurous discovery. Unlike other outdoor activities, it takes place in an environment of complete darkness, confined spaces, shifting conditions and often even beneath the surface of icy water. Cavers, speleologists or technical divers, meaning experts who are dedicated to the systematic exploration and mapping of underground spaces, regularly face unpredictable risks: from floods and falling rocks to equipment failure in inaccessible depths.

However, these dangers are not limited to professionals. Caves are often visited by amateur explorers, tourists or adventurers who underestimate the difficulty of the terrain or enter without proper equipment and experience. Quite often, they become victims of their own curiosity or lack of knowledge. And it is in such cases that tragic events occur.

In the history of underground exploration, there have been instances when an expedition ended fatally. Some explorers never returned to the surface. They died trapped in narrow shafts, stuck in flooded galleries, or succumbed to cold and exhaustion. Their fates are a reminder of courage, but also of the cruelty of nature and the limits of the human body.

In this article, I have prepared several well-known real cave stories cases where an underground adventure turned into a fight for life and ultimately death. Among the most notable are the tragedies in the caves:

These caves are where the cave stories happened:

1. Nam Talu Cave (Thailand)

This is one of the most well-known and at the same time most adventurous cave systems with flowing water in the Khao Sok National Park in southern Thailand. It is located in the area of Cheow Lan Lake and is accessible only as part of an organized tour, as it leads through a mountain massif via an underground river tunnel. Entry to the cave is allowed only with a certified guide and proper equipment.

The cave is approximately 2 300 feet (700 meters) long and is traversed from one entrance to the other. During the crossing, a person must wade through water, swim in some sections, or crawl through narrow spaces. Its interior is made of limestone and features beautiful stalactites and stalagmites. This cave is seasonally closed because during the rainy season it can flood rapidly.

On October 27, 2007, a group of 9 people entered Nam Talu Cave: 7 tourists and 2 local guides. Among the visitors were four adults from Switzerland, a 10-year-old boy from Germany, and a 16-year-old British teenager. They were seeking adventure in the cave, but instead faced a disaster that none of them anticipated.

At that time, the rainy season was already ongoing in Khao Sok, during which access to the cave is strictly limited due to the danger of sudden flooding. Despite this, the group entered the cave shortly after lunch, when everything seemed fine. The weather was good, the sky was clear, with no signs of approaching rain. At the entrance, there was no sound or sight of a storm.

However, none of them knew that a violent storm had already broken out in the mountains above the cave. Water from heavy rainfall began quickly flowing into the complex drainage system of the cave, and so, even though everything seemed safe at the entrance, water from the mountains began seeping into the cave, at first slowly, almost imperceptibly.

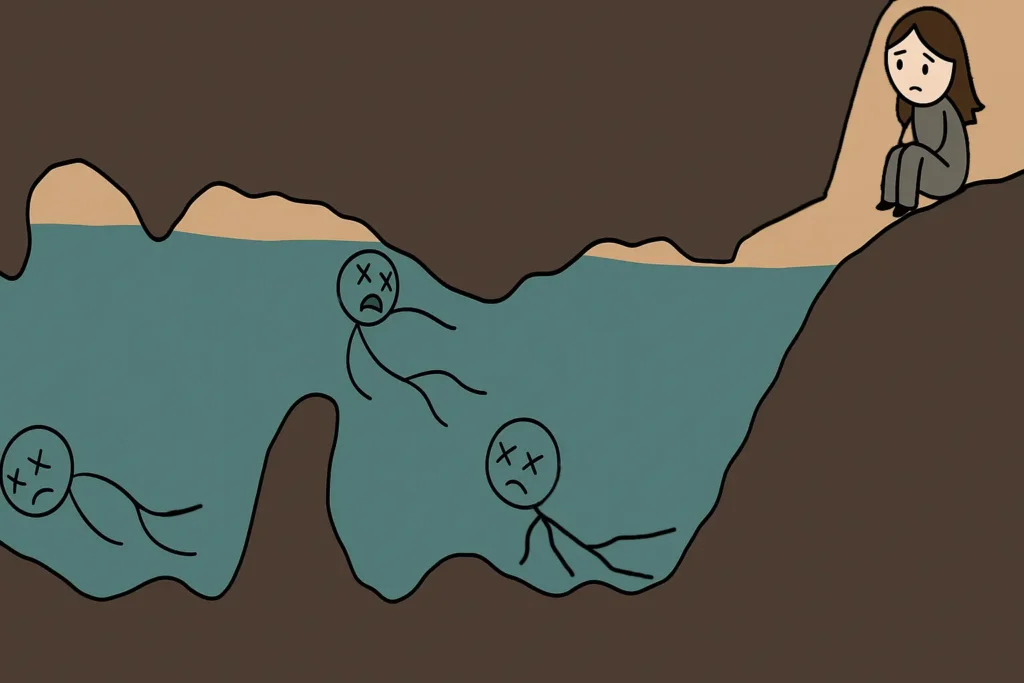

The guides did notice that the water level was rising, but decided to continue deeper into the cave. A few minutes later, however, everything changed. A strong current of water suddenly rushed through the narrow corridors and tunnels, quickly flooding the lowest sections. Panic spread through the group. The guides urged the tourists to try to reach higher parts of the cave, but it was already too late to escape.

The cave flooded within minutes. Eight people, including both guides, drowned. Only one person survived: the British teenager, who managed at the last moment to climb onto a narrow ledge high above the water level, where a small pocket of air remained. Hidden in the dark and surrounded by water, she waited there for more than 16 hours until she was rescued by emergency responders.

The body of the 10-year-old boy and the other group members were later found in the narrow flooded sections of the cave. The tragedy shocked both Thailand and the international public.

The case became a warning to all guides and tourists that the underground during the rainy season does not forgive even the smallest mistakes in judgment. Since then, entry into the cave during monsoon months has been strictly forbidden.

2. Schroeder’s Pants Cave (USA)

is a relatively small and short cave: only about 430 feet (130 meters) long and 135 feet (41 meters) deep. Despite its modest size, it was the site of one of the most well-known tragedies in American speleology. The cave received its unusual name from its discoverer, who allegedly tore his pants in it during exploration. However, in the memory of the speleological community, it remains above all as the place where a young man named James G. Mitchell died.

The group consisted of 23-year-old chemist James G. Mitchell, nurse Hedy Miller, and Harvard student Charles Bennett. Before descending into the cave, they visited George Lyon, one of the original discoverers of the cave (along with Herb Schroeder in 1947). Lyon gave them a map of the cave but failed to warn them about the extremely cold conditions inside, which later proved to be a fatal mistake.

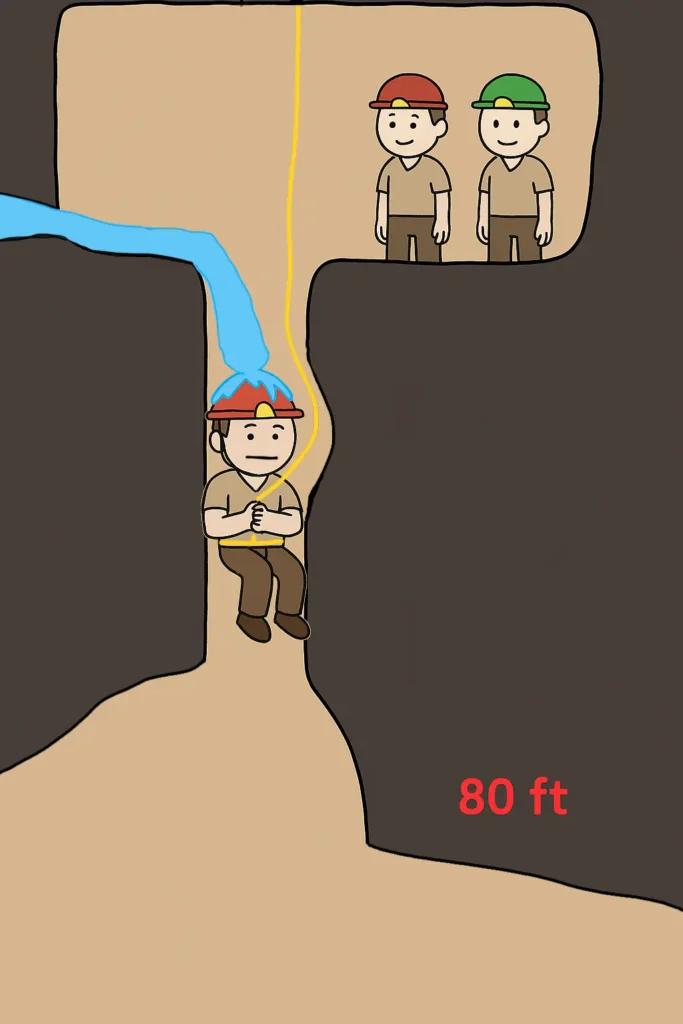

It was February 13, 1965, a freezing winter day. The group entered the cave and gradually made their way to an open vertical shaft that extended about 80 feet (24 meters) deep. Below it was another unexplored space. Mitchell decided to rappel down. But as he descended, he became stuck. He could neither go further down nor climb back up. The situation worsened due to the fact that he was directly beneath a strong flow of icy water pouring down through the shaft.

An estimated 10 gallons of icy water per minute was falling on his head. Mitchell hung on the rope, completely soaked and freezing, in darkness and cold. Given these harsh conditions, he quickly lost feeling in his hands and gradually slipped into hypothermia. His two friends tried to pull him back up, but without success. Eventually, Charles Bennett left to seek help.

Rescuers arrived at the scene, but it became clear that the rescue would be extremely dangerous. The cave was narrow, slippery, and unstable. At one point, the ceiling above the rescue team began to collapse. They assessed the situation and concluded that continuing would mean risking more lives, and a painful decision was made to leave Mitchell’s body where it hung.

The entrance to the cave was sealed with a dynamite blast, and a memorial with his name was placed directly in front of it. James Mitchell thus became a chilling symbol of the victims of cave exploration. He hung in the darkness, on a rope, alone, unburied, but not forgotten.

His body remained in the cave for almost 42 years. It was only in 2006, using new techniques, that a team of speleologists returned, reopened the cave, and succeeded in retrieving Mitchell’s remains. After decades of waiting, he was given a proper burial, and his story was finally brought to a close.

3. Gouffre de la Pierre-Saint-Martin (France)

is a colossal karst system located in the Pyrenees mountains, right on the border between France and Spain. At the time of its discovery, this cave was considered the deepest known cave in the world, and with its size, vertical shafts and unexplored galleries, it commanded great respect.

In August 1952, an international speleological expedition led by Belgian professor Norbert Casteret Cosyns set out into its depths. Among the most experienced members was 33-year-old French engineer Marcel Loubens, who served as the deputy leader of the expedition. He was a man with extensive experience in cave exploration, known for his technical thinking and bravery.

The expedition spent nearly a week underground, gradually mapping new passages, installing ropes, and descending into previously unexplored vertical tunnels in the heart of the Pierre-Saint-Martin massif. On August 27, 1952, on the sixth day of their stay, Loubens began a descent using a metal cable winch system, which was supposed to help overcome one of the deepest shafts.

During the ascent back from the shaft, in the final phase of the lift, a tragic accident occurred. The cable broke, and Loubens fell from a height of approximately 130 feet (40 meters) directly onto the rocky bottom. Miraculously, he survived, but he suffered serious injuries including a spinal fracture, was unconscious, and lay more than 1,260 feet (380 meters) underground, in one of the most inaccessible parts of the cave.

The expedition immediately launched a rescue operation. A doctor was lowered into the cave, who administered a blood transfusion and tried to stabilize him. Loubens regained consciousness and initially looked hopeful, he was alert and able to communicate.

Over the next two days, the team tried to bring him to the surface. But the narrow spaces, constant falling rocks, and technical complications made the rescue nearly impossible. The situation grew increasingly dangerous not only for the injured man but also for the rescuers, who were risking their own lives.

Despite all efforts, Marcel Loubens died on August 29, 1952, two days after the accident, deep underground, in silence and darkness, surrounded by the rocks that became his fate. After his death, the team attempted to carry his body to the surface, but the conditions were so dangerous that they ultimately decided to leave him in the cave. His body remained there for more than a year, until 1953, when another expedition, with great effort, managed to retrieve his remains and give him a proper burial in France.

A commemorative plaque was installed in the cave in his honor, and Marcel Loubens became a national hero among speleologists a symbol of courage, scientific dedication, and the tragic cost that the desire to explore the unknown often demands.

4. Jordbrugrotta (Norway)

The Jordbrugrotta cave system, also known as Pluragrotta, is located in the Plurdalen area of northern Norway. It is one of the most dangerous and technically demanding underwater cave systems in Europe. The cave was formed in a karst landscape with a combination of granite and limestone rock, creating a tangled labyrinth of narrow tunnels, shafts and sumps both above and below the waterline.

The total length of the system exceeds 1.9 mile (3 kilometers), and the deepest known point lies more than 443 feet (135 meters) below the water surface.

The water in the cave is only a few degrees above freezing, which places extreme stress on both the human body and diving equipment. Due to the complexity of the terrain, near-zero visibility, and sharp rocks in tight spaces, diving in Jordbrugrotta is possible only for highly experienced divers with specialized technical gear and thorough preparation.

February 6, 2014. On that day, five Finnish cave divers: Patrik Grönqvist, Jari Huutarinen, Jari Uusimäki, Kai Känkänen and Vesa Rantanen. Made their way into the deepest parts of the system. Their goal: to descend 430 feet (130 meters) below the surface and exit through the second entrance of the cave at Steinugleflåget. Each diver was equipped with a closed-circuit rebreather, a modern system enabling deep and long dives.

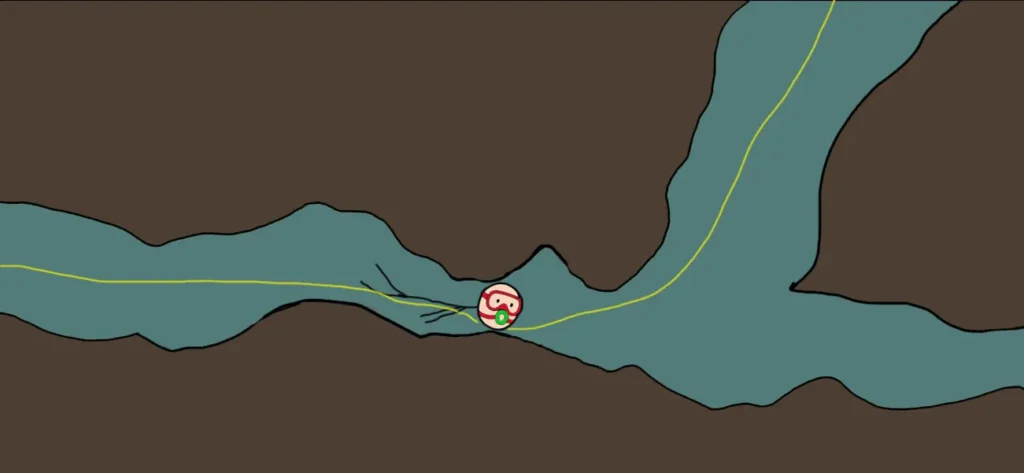

At first, everything went according to plan there was cold water, but good visibility, stable progress into the deepest parts around 360 – 430 feets (110 – 130 meters). In the deepest part of the system, approximately 360 feet (110 meters) underwater, Jari Huutarinen encountered serious trouble. While trying to switch gas mixtures or manipulate his equipment, he likely became entangled in a guide line or part of his own rebreather.

In the confined space and with zero visibility, the situation quickly deteriorated, he began to panic, was unable to free himself, and his breathing became irregular. In the chaos, his mouthpiece fell out, water entered the loop, and the rebreather failed. Patrik Grönqvist, who was nearby, immediately tried to reach him, but the space was so narrow that both of them could not fit. He tried to stabilize Jari, to give him a backup mouthpiece, but it was already too late. In a split-second decision, Patrik had to choose: die with his friend, or survive and get help. With a heavy heart, he chose to abort the dive and return the way he came.

While Patrik Grönqvist was fighting for his life on the way back through Plura, the remaining three divers: Kai Känkänen, Vesa Rantanen, and Jari Uusimäki attempted to continue along the planned route through the cave.They knew something was wrong. Patrik had vanished, and contact was lost. Their only option was to try to reach the other side of the system through a tangled labyrinth of narrow corridors, in water just a few degrees above zero, with visibility close to none.

Jari Uusimäki, one of the most experienced divers in the team, decided to turn back and find out what had happened. He wanted to locate Jari Huutarinen. But in the complex system, he became lost, disoriented, and eventually ran out of breathable gas. His body was later found, with equipment still functioning, only time was against him.

Vesa was the only one to successfully exit through Steinugleflåget, while Kai got lost. He spent an incredible 11 hours in the cave, but thanks to clear thinking, top-quality equipment, and strong willpower, he survived.

After the tragedy, authorities immediately closed the cave system. Norwegian police and rescue services declared that the bodies of the two deceased divers were unreachable and that recovery would pose too high a risk. The official mission was terminated. But the surviving team members refused to accept that. Their friends could not be left behind in eternal darkness. Following the motto “Leave no man behind,” they decided to act secretly, at their own risk, and against official orders.

Several weeks after the accident, in total secrecy, 17 Finnish divers together with Norwegian volunteers developed a detailed plan. They relocated equipment, charted routes, and once again entered the deadly underground.

Their goal was to find and recover the bodies of Jari Huutarinen and Jari Uusimäki.

Through extremely tight spaces, with zero visibility and freezing water, they truly succeeded. Over several days they swam through the entire system and brought both deceased divers to the surface. It was considered the most dangerous successful body recovery operation in the history of technical diving.

The entire process was documented in the film Diving into the Unknown (2016), as a tribute to friendship, courage, and human perseverance.

The line between curiosity and danger is thinner in caves than anywhere else. People descend into the underground with the desire to discover something new, and sometimes they find that what waits for them is not an answer, but silence. Not everyone who enters a cave comes back. But those who descended with a pure intention leave a trace – not only in the stone, but in the stories we tell after them.

If you’re interested in more intense true stories, read the shocking case of Marianne Bachmeier, the mother who took justice into her own hand

Sources: